My rave review of Nicola Griffith's imagined life of St. Hilda of Whitby, written for F5.

My rave review of Nicola Griffith's imagined life of St. Hilda of Whitby, written for F5.

26 December 2013

Hild (Nicola Griffith)

My rave review of Nicola Griffith's imagined life of St. Hilda of Whitby, written for F5.

My rave review of Nicola Griffith's imagined life of St. Hilda of Whitby, written for F5.

01 December 2013

I liked these books, 2013 edition.

This hasn't been my best year for reading or blogging, alas. But as end-of-year tradition dictates, here are the ones I did read that knocked my socks clean off! (Links go to my reviews if I managed to get them written.)

Bury Me Deep and Dare Me, Megan Abbott

The Thinking Woman's Guide to Real Magic, Emily Croy Barker

Fatale (comics series), Ed Brubaker/Sean Phillips

The Book of Dangerous Animals, Gordon Grice

NOS4A2, Joe Hill

The Wooden Shepherdess, Richard Hughes

At the Mouth of the River of Bees, Kij Johnson

The Next Time You See Me, Holly Goddard Jones

Ghost Lights, Lydia Millet

Anna and the French Kiss, Stephanie Perkins

All three Fairyland books by Catherynne M. Valente

The Weird, edited by Ann and Jeff Vandermeer

Saga (comic series), Brian K. Vaughan/Fiona Staples

Winner of the National Book Award and Amy Falls Down, Jincy Willett

Bury Me Deep and Dare Me, Megan Abbott

The Thinking Woman's Guide to Real Magic, Emily Croy Barker

Fatale (comics series), Ed Brubaker/Sean Phillips

The Book of Dangerous Animals, Gordon Grice

NOS4A2, Joe Hill

The Wooden Shepherdess, Richard Hughes

At the Mouth of the River of Bees, Kij Johnson

The Next Time You See Me, Holly Goddard Jones

Ghost Lights, Lydia Millet

Anna and the French Kiss, Stephanie Perkins

All three Fairyland books by Catherynne M. Valente

The Weird, edited by Ann and Jeff Vandermeer

Saga (comic series), Brian K. Vaughan/Fiona Staples

Winner of the National Book Award and Amy Falls Down, Jincy Willett

17 November 2013

Winner of the National Book Award (Jincy Willett)

I picked up Jincy Willett's Winner of the National Book Award used at KC's Prospero's Books, cause it was across the street from the Indian restaurant we were meeting relocated NYC friends for one of the best brunches I've ever had. Merciful Zeus, it's good. Heartbreaking and terrifying and utterly, completely hilarious.

I picked up Jincy Willett's Winner of the National Book Award used at KC's Prospero's Books, cause it was across the street from the Indian restaurant we were meeting relocated NYC friends for one of the best brunches I've ever had. Merciful Zeus, it's good. Heartbreaking and terrifying and utterly, completely hilarious.The setup could easily make for the dourest of Important Literary Novels (you know, the kind that actually win the National Book Award): it's the story of the inseparable lives of twins Dorcas and Abby Mather, one spinster librarian, one overweight sexpot, and the latter's operatic and abusive marriage to novelist Conrad Lowe--which ends in his death at her hands. Most of the novel is flashback, as Dorcas hunkers down in her library during a spectacular storm, reading the true-crime account of Abby's life and crime . . . correcting as necessary.

Dorcas is a clear-eyed, cynical narrator, and it's her Saharan wit that makes this tragic tale into a comic delight. She's eschewed sex for a lifelong love of books, and her descriptions of the bookish soul made me proclaim "YES EXACTLY" out loud multiple times. (There's a whole paean to reading Nancy Drew and world fairytales as a child that I could've written.) Willett's sharp eye for the excesses of literary culture is on display here too, as in her most recent novel, Amy Falls Down, one of my faves of the year.

And here's where I stop talking and just quote:

- "Nobody appreciates the horror of a good book dying on the wrong shelf."

- "Guy gleamed with sweat, as though mere existence on the material plane were physically exhausting."

- [A blurb on Abby's bio]: "...you will weep, you will tremble, you will cheer, and yes, you will laugh...incredible, horrifying, nauseating, and, ultimately, life-affirming and empowering. Abby Mather's triumph is our triumph.--Victoria Fracas, author of Rape, Rape, Rape

- "New Yorkers genuinely have no curiosity. They don't want to know. New Englanders do, but they'll be damned if they'll ask."

- "How well do you remember that, say, six-year-old six-hundred-pager the Times assured you was destined to become a classic? You know. The 'monumental work of fiction' that you were supposed to run, not walk, to the nearest bookstore to purchase, the book that was going to change your life, that you must read this year if you read nothing else...Winner of the National Book Award. You remember. Handleman's Jest. Parameters & Palimpsests. The Holocaust Imbroglio. We sell these babies for fifty cents apiece, or try to, seven years after they come out. We sell them because nobody has checked them out for four years."

Reading was not an escape for her, any more that it is for me. It was an aspect of direct experience. She distinguished, of course, between the fictional world and the real one, in which she had to prepare dinners and so on. Still, for us, the fictional world was an extension of the real, and in no way a substitute for it, or refuge from it. Any more than sleeping is a substitute for waking.(Parting words: two fantastic essays by Ron Hogan on criticism also made me proclaim "YES EXACTLY" a few times this week. He puts forth the notion that book critics err when they start to believe they can judge a work's intrinsic worth, suggesting the humble but still valuable alternative that I've been trying to do all along: "Instead of saying 'This and only this is how fiction should be done!' we can say 'This is a way of doing fiction that works for me,' and if we can work past that level to 'And here’s what I’ve figured out about why it works for me,' even better." Good stuff.)

03 November 2013

Scrambling up-to-date.

I'm not gonna make you listen to my excuses, because snoozers. Let's just get to the good stuff.

First, a handful of comics:

(FTC disclaimer: I received free copies of The Black Spider and The Girl Who Soared Over Fairyland and Cut the Moon in Two from NYRB Classics and Feiwel & Friends/Macmillan Books for Children, in exchange for honest reviews.)

First, a handful of comics:

- The second volume of Saga (Brian K. Vaughan/ Fiona Staples) is every bit as marvelous as the first, and I'm just leaving it at that. You should all be reading it.

- Superhero-wise, Chris insisted I'd like Flashpoint (Geoff Johns/ Andy Kubert), and indeed! The Flash is my favorite character in the DC Animated Universe, cause he's such a goofball--this story's quite different, but it's gritty without being too gritty for my taste (*cough Frank Miller cough*), an AU where Barry Allen (The Flash's forensic scientist alter ego) wakes up in a world consumed by the war between the Amazons and the Atlanteans, his old friends scattered and changed, many beyond recognition. There's the parallel-worlds fun of matching up the new characters with the familiar ones; my favorite of these was the reimagining of Captain Marvel as a ragtag bunch of teens, each possessing one of Shazam's powers. And I'm a sucker for time-travel narratives, the more twisty the better.

- And since I've read and loved all of Joe Hill's prose-only fiction, I wanted to add his just-completed comics series, Locke & Key, a try. I didn't dislike it--Hill continues to be my favorite modern horror writer--but I found myself wishing it was a novel; all Gabriel Rodriguez's dudes have really big chins and I found that super distracting. (I know, I'm not very good at reading comics.)

- Jeremias Gotthelf's The Black Spider is nineteenth-century horror in microcosm: come for the deals with the Devil and some frowny-face-earning sexism and class snobbery...stay for the titular evil arachnid literally bursting out of someone's face in gloriously florid detail. So worth it.

- And for my feelings on Catherynne M. Valente's astonishing The Girl Who Soared Over Fairyland and Cut the Moon in Two, I shall refer you to my prior gushing over the series. These are seriously among the best books for children I've ever, ever read. No, scratch that, they are among the best books period I have ever read. This one ends on a cliffhanger, which usually annoys me--but in this case, it just means there's more to come. I am already breathless with anticipation.

(FTC disclaimer: I received free copies of The Black Spider and The Girl Who Soared Over Fairyland and Cut the Moon in Two from NYRB Classics and Feiwel & Friends/Macmillan Books for Children, in exchange for honest reviews.)

07 October 2013

MEGAN ABBOTT, YOU GUYS.

This is less a review than a fan letter. And less a fan letter than the text equivalent of an animated gif of Kermit waving his arms. This one:

Because seriously, she is so good. I sought her out finally after Sarah Weinman, in the introduction of Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives, mentioned her in the same breath as Tana French and Gillian Flynn. Indeed, they form a transatlantic trifecta of badass crime fiction queens (and in my headcanon they are also a team of sensibly dressed superheroines).

The two novels I read recently, Dare Me and Bury Me Deep, are set 70 years apart--the former, among the loyalties and betrayals of a high school cheerleading squad, torn between their ruthless ex-captain and their charismatic new coach; the latter, in 1930s Phoenix, in a fictionalized account of a then-notorious murder case. Both focus on the lives of women, where men serve largely as complicating factors, and female friendships are fierce and toxic by turns.

And the prose, my God. I want to just stuff her sentences in my mouth, every one of 'em. Here's an example I've been quoting nonstop, from Dare Me:

[He] makes us dizzy, that mix of hard and soft, the riven-granite profile blurred by the most delicate of mouths, the creasy warmth around his eyes—eyes that seem to catch far-off things blinking in the fluorescent lights. He seems to see things we can’t, and to be thinking about them with great care.(Admission: this description made me picture the character as looking just like Dean Winchester. I think about Dean Winchester a lot, OK?!? LAY OFF I CAN QUIT ANYTIME)

06 October 2013

It Takes Two to Tangle & Season for Scandal (Theresa Romain)

I got to write up Theresa's two latest Regency romances for F5, here!

(FTC disclaimer: I received free copies of these books from Sourcebooks Casablanca and Zebra Books/Kensington, in exchange for honest reviews.)

Dark Lies the Island (Kevin Barry)

Wrote about Kevin Barry's phenomenal collection Dark Lies the Island for F5 here.

Wrote about Kevin Barry's phenomenal collection Dark Lies the Island for F5 here.(FTC disclaimer: I received a free copy of this book from Graywolf Press, in exchange for an honest review.)

29 September 2013

The Ocean at the End of the Lane (Neil Gaiman)

I read Neil Gaiman's The Ocean at the End of the Lane double-quick two weeks ago, knowing that whoever was next in the library queue had likely been waiting two months with bated breath like I did. Regrettably, since I didn't write it up right away, I shan't review it in much depth--luckily, pretty much of the rest of the Internet will have that covered.

I read Neil Gaiman's The Ocean at the End of the Lane double-quick two weeks ago, knowing that whoever was next in the library queue had likely been waiting two months with bated breath like I did. Regrettably, since I didn't write it up right away, I shan't review it in much depth--luckily, pretty much of the rest of the Internet will have that covered.What struck me most, though, is something I said on Tumblr: "It's a kids' book that's too scary for kids. It's as scary as a kids' book would be if a kids' book was real." (Not that Gaiman's actual kids' books aren't scary as heck: how the bloodthirsty eight-year-old I was would have rejoiced over the first page of The Graveyard Book: "There was a hand in the darkness, and it held a knife.") In fact, it reminds me a great deal of A Wrinkle in Time or Grimms' folktales, stories that frightened and shaped me as a little girl; like them, Ocean deals with dark worlds bleeding into our own, protection and sacrifice, and a child's dawning realizations about the complex imperfections of the adult world.

22 September 2013

Comics binge

Spent a lovely late-summer morning a few weeks ago sitting on the back deck, ignoring my constantly rearranged to-be-read shelf (publication date? alpha by author? how long I've had the book without getting around to reading it?), and enjoying a stack of comics. Ahhhhhh.

Saga, Volume 1, Brian K. Vaughan and Fiona Staples: Sweet Jesus, is this title good. Vaughan's story, following a couple from opposite sides of a centuries-long war, searching for a safe place for themselves and their baby girl, has drive and heart and awesome cool stuff (obviously, I would love a Lying Cat). I'm totally in love in Staples's art. And in the immortal words of LeVar Burton, you don't have to take my word for it: it recently won the Hugo award for Best Graphic Story.

Tropic of the Sea, Satoshi Kon: Weird, sweet little manga about a sleepy seaside town where the Yashiro family has spent generations protecting mermaids' eggs in exchange for filled nets for the town's fisherman. The story's tension pulls between progress and tradition, the natural world and human prosperity, and keeps the central question--do the mermaids even exist? and even if they don't, is their metaphorical significance something worthy of preservation?--ambiguous for a satisfying chunk of the tale.

Criminal: The Last of the Innocents, Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips: Jeez, how did I not know noir comics were a thing? This arc is (very very) loosely based on the world of Archie comics, but it's got grit to spare, murder and betrayal and corruption, all the delightful trappings of one of my favorite genres. And the art, which alternates between highly stylized, brightly colored Teen Shenanigans (rather less wholesome than their inspiration) and a muted, neutral and shadowy palette for an adult world rotten to its core, is phenomenal. I'll definitely be seeking out more installments of this title--luckily, there are plenty.

Helter Skelter, Kyoko Okazaki: Whoa nelly, this one's not for the faint of heart! Helter Skelter centers on supermodel Liliko, less woman than construct, whose full-body plastic surgery is beginning to fail in grotesque ways, her mind disintegrating in tandem. The art is purposefully ugly, erotic without being at all sexy, and never bothers with subtlety, fearless and assaultive in a way that's exceedingly rare in the work of female authors. I loved it, even as it made my skin crawl. I've never read anything like it. And I'm really looking forward to experiencing more of her work--Vertical publishes Pink, about a call girl with a pet crocodile, this November.

(FTC disclaimer: I received free copies of Tropic of the Sea and Helter Skelter from Vertical, Inc., in exchange for honest reviews.)

Saga, Volume 1, Brian K. Vaughan and Fiona Staples: Sweet Jesus, is this title good. Vaughan's story, following a couple from opposite sides of a centuries-long war, searching for a safe place for themselves and their baby girl, has drive and heart and awesome cool stuff (obviously, I would love a Lying Cat). I'm totally in love in Staples's art. And in the immortal words of LeVar Burton, you don't have to take my word for it: it recently won the Hugo award for Best Graphic Story.

Tropic of the Sea, Satoshi Kon: Weird, sweet little manga about a sleepy seaside town where the Yashiro family has spent generations protecting mermaids' eggs in exchange for filled nets for the town's fisherman. The story's tension pulls between progress and tradition, the natural world and human prosperity, and keeps the central question--do the mermaids even exist? and even if they don't, is their metaphorical significance something worthy of preservation?--ambiguous for a satisfying chunk of the tale.

Criminal: The Last of the Innocents, Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips: Jeez, how did I not know noir comics were a thing? This arc is (very very) loosely based on the world of Archie comics, but it's got grit to spare, murder and betrayal and corruption, all the delightful trappings of one of my favorite genres. And the art, which alternates between highly stylized, brightly colored Teen Shenanigans (rather less wholesome than their inspiration) and a muted, neutral and shadowy palette for an adult world rotten to its core, is phenomenal. I'll definitely be seeking out more installments of this title--luckily, there are plenty.

Helter Skelter, Kyoko Okazaki: Whoa nelly, this one's not for the faint of heart! Helter Skelter centers on supermodel Liliko, less woman than construct, whose full-body plastic surgery is beginning to fail in grotesque ways, her mind disintegrating in tandem. The art is purposefully ugly, erotic without being at all sexy, and never bothers with subtlety, fearless and assaultive in a way that's exceedingly rare in the work of female authors. I loved it, even as it made my skin crawl. I've never read anything like it. And I'm really looking forward to experiencing more of her work--Vertical publishes Pink, about a call girl with a pet crocodile, this November.

(FTC disclaimer: I received free copies of Tropic of the Sea and Helter Skelter from Vertical, Inc., in exchange for honest reviews.)

15 September 2013

I Am a Cat (Soseki Natsume)

Hmm, I wonder why I wanted to read this book? :)

Soseki Natsume's I Am a Cat was published serially from 1905-06, and (I'm reliably informed) is considered a modern classic in Japan, a book pretty much everyone has read--I'm super proud of myself for picking up that a curmudgeonly tomcat in the awesome manga Chi's Sweet Home is a homage to this nameless feline narrator's grouchy mentor, Rickshaw Blacky.

The novel's actually less Kitty Adventures and more a human-focused satire, as the cat observes (with jaded eye, natch) the humans of his acquaintance, most notably his schoolteacher owner, called "Mr. Sneaze" in the translation I read--I'm pretty sure everyone's names are punny in the original, but alas, I can't read Japanese and am unlikely ever to learn. Though Sneaze only teaches high school English (and is relentlessly mocked by his students), he considers himself an intellectual and a scholar, and hangs out with a gang of other mediocrities with similarly inflated views of themselves. There's Waverhouse, whose principal joy in life is telling outrageous stories with a straight face and then laughing at those hapless enough to take him seriously; prolific poet Beauchamp Blowlamp, happy to turn his verse to any occasion; perpetual grad student Avalon Coldmoon, whose thesis on "The Effects of Ultraviolet Rays upon Galvanic Action in the Eyeball of the Frog" is held up by his inability to grind a chunk of glass into a perfect sphere; Zen philosopher Singleman, who always has a portentous phrase at the ready. They endlessly discuss life, love, literature, politics--the book takes place during the late Meiji era, when Japan was first opening up to Western influence, a sudden mixing of traditions that caused massive cultural upheaval. There's a crazy chapter, for instance, that centers on Sneaze's battles with the students of the next-door boys' school, who are constantly hitting their baseballs over his fence.

It took me a few weeks to get through the book--it's long, and the register's rather formal, and I found it slow going at first...then somewhere around a third of the way through, I just fell in love. Part of that was getting used to the pace, which is somehow both madcap and leisurely (that's a cat for ya!); part of that was figuring out exactly what kind of book I was reading, picaresque and comic in a way that reminds me (and this is high praise) of Sterne's Tristram Shandy--which is, in fact, name-checked in the text! And while perhaps there's not as many feline shenanigans as I'd expected, when Soseki does turn his eye to cat behavior, he's got it down: "[H]uman beings being the nitwits that they are, a purring approach to any of them, either male or female, is usually interpreted as proof that I love them, and they consequently let me do as I like, and on occasions, poor dumb creatures, they even stroke my head." Or a lengthy passage about the cat's fitness regimen, assisted by an unwilling mantis:

[F]aced with such aggression, I have no choice but to give him a whack on the nose. My foe collapses, falls down flat with his wings spread out on either side. Extending a front paw, I hold him down in that squashed-face position whilst I take a little breather. Myself at ease again, I let the wretched perisher get up and struggle on. Then, again, I catch him. . . . Eventually, the mantis abandons hope and, even when free to drag himself away, lies there motionless. I lift him lightly in my mouth and spit him out again. Since, even then, he just lies loafing on the ground, I prod him with my paw. Under that stimulus the mantis hauls himself erect and makes a kind of clumsy leap for freedom. So once again, down comes my quick immobilizing paw. In the end, bored by the repetitions, I conclude my exercise by eating him.And there's a gimlet eye for the people, too--I particularly loved the still-applicable passage about how "[m]ore often than not, modern poets are unable to answer even the simplest questions about their own work. Such poets write by direct inspiration, and are not to be held responsible for more than the writing. Annotation, critical commentary, exegesis, all these may be left to the scholars. We poets are not to be bothered with such trivia." Hee hee.

N.B. (and SPOILER ALERT): the book doesn't end well for the cat! I'm usually annoyed when the introduction to a book gives away the ending, but I'm glad I knew that going in, so I'm passing the warning along to you.

10 September 2013

Cat Sense (John Bradshaw)

Whelp, that's 80% of my Christmas shopping done...because nearly everyone I know needs to read Cat Sense. (And my eARC is gonna expire, so I need to get a copy for myself too!)

Whelp, that's 80% of my Christmas shopping done...because nearly everyone I know needs to read Cat Sense. (And my eARC is gonna expire, so I need to get a copy for myself too!)It's no secret that I'm a cat lady. I mean, I love dogs too, and our rabbit Bernie is a hoppity cilantro-noshing jeans-nibbling ambassador for his entire species, but kitties are the beasts closest to my heart. And I love learning about them--I remember dissecting a cat my first semester in college and then coming home at Christmas to our own kitties, running my hands over them and whispering, "I know what you look like inside." (OK, now I've written that, I sound like a serial killer. It was very awestruck and appreciative, I promise!) I've often thought they are really far better animals than we are--their perfect adaptations to hunting, how their sleek musculature rolls under their skin, those enormous eyes. And, of course, I've had important relationships with several, especially my wee yell-y Siamese, Julie, with whom I lived for sixteen years; I will never receive her kind of devotion from another creature. She helped me become who I am.

All of which is to say, of course I wanted to read this book the moment I discovered it existed. I was richly rewarded: Bradshaw's account of the history, biology, and behavior of the domestic cat is extensive and full of buttonhole-worthy tidbits--and his ultimate argument that, in order to preserve their future, we need to start thinking seriously about actually finishing the job of domestication by breeding cats for sociability, really opened up a new avenue in my thinking. (And made me happy to think that Benny, who wasn't neutered until he was around four, almost certainly has descendants out there, and they must be terrific cats!)

Here, have some kitty facts that I've been bugging my husband with while he plays Candy Crush Saga:

- You know who was totally all about the orange tabbies? THE FREAKING VIKINGS, THAT'S WHO. Brains' new nickname is obviously "my little Viking cat."

- 4000 years ago, the Egyptians developed the first word for "domestic cat," Miw; soon, it was also a name for girls. Same thing happened with the Romans, for whom "Felicula" (little kitten) was a common girls' name about two millennia ago.

- We all saw that medieval manuscript the kitty walked across with ink on its paws, right? Bradshaw cites several examples of places and times (like first-century Britain) where we know cats were well integrated into society because they left footprints on clay tiles.

- We all know cats can see better in dim light than we do...but it'd never occurred to me that they see worse than we do in full daylight. Obvious in retrospect.

- Oh, also I read about the most arduous scientific experiment ever, testing how the amount of handling kittens get in their second month of life affects their relationship with humans. It involved picking up 29 eight-week-old kittens (who are at their MAXIMUM CUTENESS), to see what they'd do. Science is awesome.

I suppose it's not too much of a stretch to say that this book is highly recommended for cat folk--but I'm gonna say it anyway. Also, meow.

(FTC disclaimer: I received a free copy of this book from Basic Books, in exchange for an honest review.)

09 September 2013

The Waking Dark (Robin Wasserman)

I loved Robin Wasserman's last novel, the occult thriller The Book of Blood and Shadow, so of course I scrambled to pick up The Waking Dark, a harrowing horror story set in small-town Kansas, and read it in a night or two. And while I generally like a soupçon more of the straight-up supernatural chocolate in my horrific peanut butter, Waking Dark is definitely a first-rate novel: heartbreaking, gut-wrenching, thought-provoking, spine-tingling--really a workout for all your internal organs.

I loved Robin Wasserman's last novel, the occult thriller The Book of Blood and Shadow, so of course I scrambled to pick up The Waking Dark, a harrowing horror story set in small-town Kansas, and read it in a night or two. And while I generally like a soupçon more of the straight-up supernatural chocolate in my horrific peanut butter, Waking Dark is definitely a first-rate novel: heartbreaking, gut-wrenching, thought-provoking, spine-tingling--really a workout for all your internal organs.

To begin with--quite literally--it has one of the best opening chapters I've ever read. It's an account of what Oleander, Kansas, refers to in its aftermath as "the killing day," when five ordinary citizens murder eight others--with shotgun, knife, fire, automobile, pillow--before turning on themselves. Five teenagers (and let me tell you, the age of the protagonists is the only thing making this YA) are at these scenes of sudden carnage: Daniel Ghent, son of the alcoholic, apocalyptic Preacher, who tries to protect his little brother from the worst excesses of their father and the world; Jule Prevette, whose notorious family cooks meth on the decaying outskirts of Oleander; Ellie King, fervently Christian, who witness her reverend crucifying a man before burning the church down with him inside; closeted football player Jeremiah West, whose boyfriend Nick is mowed down by a car; and Cassandra Porter, killer and victim, who smothers the infant boy she's babysitting before jumping out a second-story window. She is the only murderer to survive, incarcerated in what she believes to be a mental hospital, with no explanation to offer.

Oleander buries their dead, as they have done before. In fact, the current town is built on the ruins of the first Oleander, which burned to the ground in 1899, taking 1,123 inhabitants with it--the details of the catastrophe lost to history. A year after the killing day, a tornado sweeps through town, an EF-5 that destroys entire neighborhoods. And a facility on the edge of town, the one Cass has spent a year in, the one which she realizes was never a psych ward at all, as a "doctor" leads her out of the collapsing building and they step over armed and uniformed corpses. After the storm, Oleander finds itself cut off from the outside world--no phones, no internet, tanks and men with guns blocking the roads out. No one tells them why.

But it's clear that things are different: tempers shorten, speculations grow wilder, suspicion and violence creep into the hearts of the townspeople. As their small society begins to spiral out of control, Daniel, Jule, Ellie, West, and Cass, seemingly unaffected by the paranoia and rage flooding Oleander, search for answers. What has happened here? Has the Devil taken over? Or is it simply the darkness in every human heart, brought to the surface and let out to play?

I suppose you could call this a dystopia--Oleander certainly suffers the end of its little world--but like Blood and Shadow before it, Waking Dark is a "kids' book" with serious philosophical consideration behind it. At its core, it grapples with the central questions of human nature: are we, in our most essential selves, good or evil? How are these terms--self, good, evil--even defined? Wasserman doesn't offer answers, and doesn't shield her characters from the consequences of their own actions, giving us a tale that's complex, propulsive, and often genuinely frightening.

P.S. As a native Kansan, I've gotta point out a couple of inaccuracies--there's more than one abortion provider in the state (though not many more); and for Pete's sake, novelists of my acquaintance, the principal crop of this state is WHEAT, not corn. But Wasserman more than makes up for these quibbles with this haunting passage:

Tornadoes, unlike hurricanes, do not get named. A hurricane is an unwelcome houseguest, one you see coming. You can watch it from afar, learning its habits and its nature. The hurricane is the enemy you know well enough to hate, the lover who inevitably betrays. The tornado is the stranger at the door with a knife. It has no features, no habits, no face.I knooooooow. That second-to-last sentence I will carry with me forever.

(FTC disclaimer: I received a free copy of this book from Knopf Books for Young Readers, in exchange for an honest review.)

26 August 2013

Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives (ed. Sarah Weinman)

(I know: that cover! That title! How perfect.)

(I know: that cover! That title! How perfect.)

Editor Sarah Weinman embarked on Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives as a response to "the current crop of crime writers who excite and inspire me the most"--women like Gillian Flynn, Tana French, and Laura Lippman (fun fact: I once sold a Lippman novel to Kyra Sedgwick! Mr. Bacon was also present.) Many of these authors work in what's known as "domestic suspense," crime fiction that takes place in ordinary spaces and lives, splitting the difference between hard-boiled and cozy--and very often centering on the ambitions and frustrations of women.

Yet while these modern authors sell like lovely bloodthirsty hotcakes, their predecessors--women writers working at mid-century who invented domestic suspense--have been largely forgotten. Weinman sets out to right this wrong, selecting fourteen stories by as many authors, written between the 1940s and mid-1970s. I'd only heard of Patricia Highsmith, whose inclusion here is surprising, as she made a name for herself writing about men, and (of course) Shirley Jackson, whose "Louisa, Please Come Home" deserves to be read as much as "The Lottery." Some of the others were critically acclaimed bestsellers in their day, such as Vera Caspary--"Sugar and Spice" is a skillful portrait of toxic friendship, though I wish it had a more ambiguous ending--and Edgar-winning Charlotte Armstrong. The latter's "The Splintered Monday" contains my favorite line in the collection: "Bobby [got] into his chair in a young way that was far more difficult a physical feat than simply sitting down." I loved Elizabeth Saxby Holding's "The Stranger in the Car," where all the women know more than they let on, and the male protagonist knows far less than he thinks he does, and Miriam Allen Deford's "Mortmain" is deliciously malicious and unexpected.

Weinman's introduction is a bit simplistic in its history for me, mostly adhering to the tired narrative that feminism was an invention of the 1960s, and twice her notes on the individual stories have small but crucial errors in her plot summaries. Despite these small quibbles, her analysis of the subgenre is excellent, and she can certainly sling a sentence herself, as here: "The bombast of global catastrophe, the knight-errant detective's overweening nobility, of the gaping maw of total self-annihilation has no place in these stories." In lifting these writers from obscurity, she's done a great service to mystery readers, and to the writers themselves.

(FTC disclaimer: I received a free copy of this book from Penguin, in exchange for an honest review.)

15 August 2013

The Thinking Woman's Guide to Real Magic (Emily Croy Barker)

Reviewed Emily Croy Barker's excellent debut, The Thinking Woman's Guide to Real Magic, here for F5.

Reviewed Emily Croy Barker's excellent debut, The Thinking Woman's Guide to Real Magic, here for F5.11 August 2013

07 August 2013

The Prague Cemetery (Umberto Eco)

Umberto Eco's latest novel, The Prague Cemetery, left me with somewhat muddled reactions, which I'll try to talk out here. It's told as a diary in dialogue--that is, a certain Piedmontese Captain Simonini, gourmand and forger, takes the advice of a "Doctor Froïde" he met once and begins to reconstruct the events of his life, in an attempt to regain recent memories he seems to have lost. Soon, he finds interpolations from a cleric, Abbé Dalla Piccola, who may or may not be himself in disguise. The two weave a tale of far-reaching conspiracy, including their involvement with Garibaldi, the Paris Commune, and the Dreyfus Affair, and hatred: of Freemasons, of Jesuits, of women, Russians, Germans, French, Italians, and above all, the Jews. Having gathered calumnies from various European sources for decades, Simonini eventually authors the all-too-influential hoax document The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, used as justification for anti-Semitic violence to this day (in fact, I'm a little grossed out that this page will show up somewhere when you Google it. Unfortunately, I'm sure it's far down on the list).

Umberto Eco's latest novel, The Prague Cemetery, left me with somewhat muddled reactions, which I'll try to talk out here. It's told as a diary in dialogue--that is, a certain Piedmontese Captain Simonini, gourmand and forger, takes the advice of a "Doctor Froïde" he met once and begins to reconstruct the events of his life, in an attempt to regain recent memories he seems to have lost. Soon, he finds interpolations from a cleric, Abbé Dalla Piccola, who may or may not be himself in disguise. The two weave a tale of far-reaching conspiracy, including their involvement with Garibaldi, the Paris Commune, and the Dreyfus Affair, and hatred: of Freemasons, of Jesuits, of women, Russians, Germans, French, Italians, and above all, the Jews. Having gathered calumnies from various European sources for decades, Simonini eventually authors the all-too-influential hoax document The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, used as justification for anti-Semitic violence to this day (in fact, I'm a little grossed out that this page will show up somewhere when you Google it. Unfortunately, I'm sure it's far down on the list).Simonini is the only entirely fictional character in the novel, who has a great talent for forgery and creating "original documents" by developing and changing old conspiracies to fit what his audience wants to hear (theorizing that there is really only one conspiracy theory, requiring only tweaking to work for any hated group or scenario). By doing this, he becomes the common thread throughout much of the great paranoias of nineteenth-century Europe.

The thing is, I'm not sure how much the book works as a novel. The mystery of whether Simonini and Dalla Piccola are the same person, and what trauma led to their splitting, pales in interest beside the complex web of bigotry and fear and intrigue that runs throughout--but it's the non-fiction that's most compelling (and horrific). Which leads to the question: why not write it is as non-fiction? Eco would have had to sacrifice some narrative drive, of course, but wouldn't have lost the story. And in a way, attributing these wide-ranging machinations to the work of a single man lessens their impact; though he's certainly aided and abetted by various authors, journalists, and secret police, Simonini is ultimately responsible for the Protocols, rather than their being a collaborative result of centuries of anti-Jewish sentiment. It is, I think, a great lie that we've been told, that Hitler was an anomaly, rather than the culmination of a European tradition of hate and persecution. He just perfected the means.

Thus: while I didn't find Prague Cemetery entirely satisfying, I'm still glad I read it, unsettling as it was. But if you just want a great conspiracy thriller, you should just (re)read Foucault's Pendulum.

01 August 2013

18 July 2013

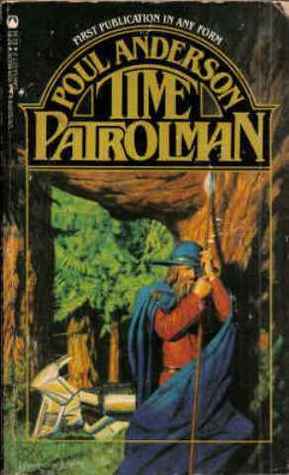

Briefs: The Iron Bridge (Anton Piatigorsky), Limit Vol. 6 (Keiko Suenobu), & Time Patrolman (Poul Anderson)

Anton Piatigorsky's The Iron Bridge dramatizes small incidents from the teenage years of six brutal 20th-century dictators: Idi Amin, Pol Pot, Mao Tse-Tung, Josef Stalin, Rafael Trujillo, and Adolf Hitler. It's--well, I want to call it a "fun" project, is that OK? perhaps the even less descriptive "interesting"? It's also a bit MFA thesis-y, to be honest. Perfectly competent writing, but little fervor (except in Hitler's off-the-cuff diatribes in "Incensed," but he's also the easiest subject, right?), and a certain predictability to the whole endeavor; suffice to say it didn't knock my socks off. Though I may have been spoiled by the genius of Richard Hughes' characterization of Hitler in The Human Predicament.

Anton Piatigorsky's The Iron Bridge dramatizes small incidents from the teenage years of six brutal 20th-century dictators: Idi Amin, Pol Pot, Mao Tse-Tung, Josef Stalin, Rafael Trujillo, and Adolf Hitler. It's--well, I want to call it a "fun" project, is that OK? perhaps the even less descriptive "interesting"? It's also a bit MFA thesis-y, to be honest. Perfectly competent writing, but little fervor (except in Hitler's off-the-cuff diatribes in "Incensed," but he's also the easiest subject, right?), and a certain predictability to the whole endeavor; suffice to say it didn't knock my socks off. Though I may have been spoiled by the genius of Richard Hughes' characterization of Hitler in The Human Predicament. Limit Vol. 6 (publishes July 23) wraps up the "Mean Girls meets Lord of the Flies manga series I've been devouring since the beginning. I'd worried mid-series that the story would suffer from the marooned girls' discovery that a male classmate survived as well, cause boys ruin everything, but then there was a murder, and paranoia, and red herrings, and I was hooked again. And I found this last volume utterly satisfying and sweet--I may have even shed a few tears.

Limit Vol. 6 (publishes July 23) wraps up the "Mean Girls meets Lord of the Flies manga series I've been devouring since the beginning. I'd worried mid-series that the story would suffer from the marooned girls' discovery that a male classmate survived as well, cause boys ruin everything, but then there was a murder, and paranoia, and red herrings, and I was hooked again. And I found this last volume utterly satisfying and sweet--I may have even shed a few tears. Time Patrolman came into my life as a Kickstarter reward, from Ad Astra Books and Coffee in Salina, KS. It's really two novellas rather than a single story: the first, "Ivory, Apes, and Peacocks," takes place in 950 BC in the flourishing Phoenician city of Tyre. Manse Everard has come there to investigate a bomb sent from the future by temporal terrorists unknown; as a member of the Time Patrol--an organization formed to protect the integrity of humanity's history--he must track down the perpetrators, in time as well as space, before they carry out their threat to destroy the whole city, with the millenia of repercussions such a catastrophe would create. It's a fun historical/sci-fi detective story, with a great sense of place.

Time Patrolman came into my life as a Kickstarter reward, from Ad Astra Books and Coffee in Salina, KS. It's really two novellas rather than a single story: the first, "Ivory, Apes, and Peacocks," takes place in 950 BC in the flourishing Phoenician city of Tyre. Manse Everard has come there to investigate a bomb sent from the future by temporal terrorists unknown; as a member of the Time Patrol--an organization formed to protect the integrity of humanity's history--he must track down the perpetrators, in time as well as space, before they carry out their threat to destroy the whole city, with the millenia of repercussions such a catastrophe would create. It's a fun historical/sci-fi detective story, with a great sense of place. Still, I liked the second tale, "The Sorrows of Odin the Goth," much better--its emotionally engaging characters and immersion in the everyday life of ordinary people insignificant to history remind me of Connie Willis's Oxford time-travel stories. Carl Farness is recruited to the Time Patrol as an academic; formerly a professor of Germanic philology, he wants to track down the truth of events among the fourth-century Ostrogoths that gave rise to legends recorded centuries later. But while there, he falls in love, and when Jorith dies in childbirth, he becomes determined to protect his offspring, born 1500 years before him. His entanglement with his own descendants gets him in trouble, of course, but it's not till the very end that he realizes how great the damage he's done, and the one agonizing choice that remains to him to fix things. Sad, beautiful, and complicated (I mean, the tenses alone!).

(FTC disclaimer: I received free copies of The Iron Bridge and Limit Vol. 6 from Steerforth and Vertical, respectively.)

11 July 2013

The Wooden Shepherdess (Richard Hughes)

Oh, gosh. Guys, can get on making literary necromancy a thing? Because Richard Hughes having the bad luck to die before finishing the projected third volume of The Human Predicament, I think, ranks up there with Gogol's burning the second part of Dead Souls (and then dying himself before he thought better of it) in terms of woefully unfinished masterpieces. The two volumes he published in 1961 (The Fox in the Attic) and 1973 (The Wooden Shepherdess) are already a 20th-century War and Peace, sans theory-of-history digressions and plus a wry wit Tolstoy wouldn't know if it bit him in the beard. It's somehow both epic and intimate, gorgeously written, and Hughes has taught me more about the internal machinations of the Nazi Party, and contemporaneous British parliamentary politics, than history class ever did. (Not to knock my European History teacher at all. Dude was awesome.)

Oh, gosh. Guys, can get on making literary necromancy a thing? Because Richard Hughes having the bad luck to die before finishing the projected third volume of The Human Predicament, I think, ranks up there with Gogol's burning the second part of Dead Souls (and then dying himself before he thought better of it) in terms of woefully unfinished masterpieces. The two volumes he published in 1961 (The Fox in the Attic) and 1973 (The Wooden Shepherdess) are already a 20th-century War and Peace, sans theory-of-history digressions and plus a wry wit Tolstoy wouldn't know if it bit him in the beard. It's somehow both epic and intimate, gorgeously written, and Hughes has taught me more about the internal machinations of the Nazi Party, and contemporaneous British parliamentary politics, than history class ever did. (Not to knock my European History teacher at all. Dude was awesome.)The Fox in the Attic ended with the Munich Putsch, and The Wooden Shepherdess somewhat accelerates the pace, climaxing eleven years later with the Night of the Long Knives (memorably and mythically depicted in Visconti's The Damned). I say "somewhat," because while several months or even years may be dispatched in summary, there are small scenes and set pieces along the way that seem to proceed in real time. The book begins in Prohibition-era America, where the 24-year-old quasi-hero of Attic, Augustine, has ended up after being mugged on a Breton dock and unceremoniously dumped down the hatch of a rum-running boat. Hiding out due to his lack of papers and his illicit means of arrival, he soon finds himself the "elderly mascot" of a pack of hard-drinking, promiscuous, utterly baffling teenagers--"self-sufficient as eagles, unarmored as lambs." This setup leads to perhaps the best literary car chase of all time (I mean, can you think of another one?), and Augustine's deflowering, an encounter he feels a "cold-porridge parody" of his pure love for his Bavarian cousin, Mitzi, whose entry into a Carmelite convent forms another, rather less raucous, thread.

The novel also continues the story of Augustine's sister, Mary, her MP husband, Gilbert, and their daughter, Polly, and adds a new backdrop--the slums of Coventry; at one point Hughes segues between the two brilliantly with "Yes, the ways of the rich man are known to be full of trouble; but even the poor have their cares." And while the rich and poor of Great Britain have their troubles and cares, while Augustine has adventures in Morocco and grows ever more aimless, Hitler slowly continues to climb to absolute power. And not in the background, either--Hughes is totally unafraid to hash out history in narrative, to flesh out real people as characters, to try to figure out not just the how but the why of it, with the chilling hindsight that 30s Europe simply didn't have. An ambitious undertaking, to say the least--but one in which he unambiguously succeeds.

09 July 2013

04 July 2013

Wives and Daughters (Elizabeth Gaskell)

Wives and Daughters was the last book I started in my recent travels, on the train back to Kansas from New Mexico. I think it was recommended to me ages ago when I read Fathers and Sons? So yeah, the Project Gutenberg ebook's been sittin' on the ol' Nook for a while. Glad I finally got to it, though!

Wives and Daughters was the last book I started in my recent travels, on the train back to Kansas from New Mexico. I think it was recommended to me ages ago when I read Fathers and Sons? So yeah, the Project Gutenberg ebook's been sittin' on the ol' Nook for a while. Glad I finally got to it, though!Set in the 1820s in an English country village, Wives and Daughters is mostly the story of Molly Gibson, daughter of the local surgeon. I'm not gonna lie, she's pretty annoying, v. much in the Sweet Gentle Victorian Heroine mold, which can often read as spineless to a millenial harridan like me. She's hardly insufferable, though, and she's surrounded by some great female characters--and male as well, in the persons of Squire Hamley and his two sons, Osborne and Roger, all good dudes.

But as the title tells us, the women in the book may be defined by their relationships to men, they occupy their own feminine spaces, and it's in these that the novel largely dwells. Mr. Gibson's appallingly self-centered second wife sometimes shades into evil-stepmother territory, it's true; her daughter, Cynthia, however, defies stereotype. Cynthia is flirtatious, and thoughtless at time, but she and Molly become as close as sisters, despite their differences (this diverse-sibling relationship is mirrored by the Hamley boys). I loved Cynthia (and I loved that everybody thinks her name is totally out there): she knows who she is, and she knows her own mind, flaws and all.

(Also gotta give a thumbs-up to the happily unmarried Miss Browning, who says at one poit, "I am rather inclined to look upon matrimony as a weakness to which some very worthy people are prone.")

One warning should you decide to read this one--it was published serially, starting in August 1864, and Elizabeth Gaskell died of a heart attack in November 1865 without finishing it. It's almost there--you can tell what's going to happen--but it's really a shame she didn't get to write it.

*For the standard by which I now measure heroine insufferability, read** the sentimental journey of Ellen Montgomery, protagonist of Susan Warner's 1850 The Wide, Wide World--America's first bestseller!

**No, please don't read it, it's awful. Like, in one of the first chapters, Ellen's mother chides her because Ellen says she loves her mom more than she loves Jesus, and her mom is all, "I love Jesus more than I love you." SERIOUSLY THIS IS A THING THAT HAPPENS AUGH

14 June 2013

Readin' across America.

On the last day of May, my husband and I packed up a van with our critters (two cats and a rabbit) and left Brooklyn for my hometown of Wichita, KS. 1400 miles later, we took up temporary residence in my parents' basement, which I'm way more excited about than y'all think (we Perlebergs are a tight-knit, loquacious, loud, weird clan). Five days later, in the wee-est of hours, we boarded the Amtrak's Southwest Chief in the nearby burg of Newton, and went another 600 miles to visit my sister and brother-in-law in Santa Fe, NM. And back, six days later.

What I'm getting at here is: Having traveled roughly 2600 miles in the past two weeks, I have read a LOT of books recently. And I know I'm never going to write them all up individually, but I don't want 'em to go entirely uncommented on, so. Comments!

I started with Jincy Willett's July release, Amy Falls Down, which I loved to pieces--but I'm reviewing it for Wichita's alt-weekly F5, so I'll link to that when it's up.

Basti, Intizar Husain: NYRB Classics sucked me in by describing this as "the great Pakistani novel." And besides, I've only ever read one book translated from Urdu (Naiyer Masud's Snake Catcher). The book follows Zakir through roughly forty years, from pre-Partition British India to the 1971 war that gained Bangladesh (formerly East Pakistan) its independence. There are also dreamlike, surreal flashbacks to the Delhi of 1857, convulsed by the Indian Rebellion (if you're my dad and know Indian history primarily through British eyes, you'll have known it as "the Sepoy Mutiny" until you made Pakistani friends at work and they're like, "Uhhhh, NO"). The narrative shuttles back and forth in time, space, and culture (the references, helpfully compiled in a six-page glossary, derive from Muslim, Hindu, and even Buddhist religious and folk traditions)--it can be difficult to orient oneself, although Pritchett has helped a lot by adding lacunae between sections and ellipses to indicate fantasy/flashback passages. A fascinating read--like all my favorite translated literature, it makes me want to learn the original language so I can read it again.

Once Upon a Tower, Eloisa James: The latest in James's generally brill fairytale series! This one has elements of Rapunzel (obvy). I lurved the hero, Gowan, because he is Tall and a Virgin and SCOTTISH--his height led me to just picture Sam Winchester (IN A KILT OMGGGGGG) the whole way through, endearing him further. Since I was more into him than her--Edie, a talented cellist trapped in an era when women had to play it sidesaddle if they wanted to do so in public--I thought everybody was too hard on him in the third act. YMMV, as they say.

Pigeons, Andrew D. Blechman: You know, I don't miss much about NYC qua NYC--but I sort of love pigeons. To quote myself from Facebook: "they are honestly really pretty birds, and I think it's cool how well they've adapted to this hyperurban habitat, such that they're most of the wildlife landscape of the city. Plus, during mating season, watching the dude pigeons fluff up their feathers and do their little head-bobbing HEY HEY HEY LADIEZZZZ at the females, who never look the slightest bit interested . . . free entertainment! So hilarious." This book, then, was a goodbye-Big-Apple gift to myself. It's very much in the recent tradition of One-Subject Non-Fic (e.g. Mark Kurlansky's Salt or Victoria Finlay's Color: A Natural History of the Palette), and as such is anecdotal. Blechman visits the racing lofts of Brooklyn, the Westminster Kennel Club of pigeons shows in Pennsylvania, gun clubs that indulge in live pigeon shoots, a pair of CRAZY old ladies moseying around Manhattan dumping pounds of birdseed on the ground for city pigeons...great stuff. AND he debunks the "flying disease factory" myth that has maligned the rock dove over the past few decades: yeah, pigeon poop can breed bacteria and fungi in large quantities. But that's sort of the favorite hobby of excrement in general, isn't it? Handling a pigeon won't get you sick. SO THERE.

Red Shift, Alan Garner: THIS BOOK. Guys, I don't even know what to say about this book. It threads through three different times--Roman Britain, the English Civil War, and 1970s England--connected by a place (Mow Cop, a village on the Cheshire/Staffordshire border) and an artifact (a stone axe, 3500 years old, hidden and found between the timelines). But they're also bound by madness, and mysticism, and one of the strangest narrative flows I've ever muddled through. And I don't mean "muddled through" in a bad way, somehow--and when I say "I didn't get it, but I'm not sure there's anything to get," I don't mean there's nothing there, simply that confusion and immersion and a feeling of slipping through consciousnesses that you can't quite get a hold of are absolutely what the reader's supposed to feel. What Garner wants. It's crazy good.

Guarded (Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Season 9, Volume 3), Andrew Chambliss & George Jeanty, Jane Espenson, Drew Z. Greenberg & Karl Moline: Picked this up at Santa Fe's adorbs comics shop, Big Adventure Comics (along with the first issue of Brian K. Vaughan and Fiona Staples' Saga, which I will be reading more of POSTHASTE). I'd previously purchased Volumes 1 & 2 (Freefall and On Your Own respectively), and I've liked this season so far; it's MUCH more grounded than the whee-no-cable-budget insanity into which Season 8 devolved--and, in fact, shows Buffy finally dealing with the fact that she's never become an adult, that despite how well she handles herself with Bad Badness (in the aftermath of magic's banishment, vampires are cut off from their demonic source, and have become feral, indiscriminate butchers), she's terrible with responsibilities like jobs and rent and all the trappings of maturity. Me too, lady, me too. (The second arc features a bait-and-switch storyline that maddeningly shies away from a serious and heartbreaking decision she's faced with--and I totally understand that it was the last straw for some fans--so be forewarned. Me, I'm sort of a helpless Whedon apologist, so I'm willing to press on.)

Back in Wichita now, I'm halfway through Elizabeth Gaskell's 1865 Wives and Daughters. More to come!

What I'm getting at here is: Having traveled roughly 2600 miles in the past two weeks, I have read a LOT of books recently. And I know I'm never going to write them all up individually, but I don't want 'em to go entirely uncommented on, so. Comments!

I started with Jincy Willett's July release, Amy Falls Down, which I loved to pieces--but I'm reviewing it for Wichita's alt-weekly F5, so I'll link to that when it's up.

Basti, Intizar Husain: NYRB Classics sucked me in by describing this as "the great Pakistani novel." And besides, I've only ever read one book translated from Urdu (Naiyer Masud's Snake Catcher). The book follows Zakir through roughly forty years, from pre-Partition British India to the 1971 war that gained Bangladesh (formerly East Pakistan) its independence. There are also dreamlike, surreal flashbacks to the Delhi of 1857, convulsed by the Indian Rebellion (if you're my dad and know Indian history primarily through British eyes, you'll have known it as "the Sepoy Mutiny" until you made Pakistani friends at work and they're like, "Uhhhh, NO"). The narrative shuttles back and forth in time, space, and culture (the references, helpfully compiled in a six-page glossary, derive from Muslim, Hindu, and even Buddhist religious and folk traditions)--it can be difficult to orient oneself, although Pritchett has helped a lot by adding lacunae between sections and ellipses to indicate fantasy/flashback passages. A fascinating read--like all my favorite translated literature, it makes me want to learn the original language so I can read it again.

Once Upon a Tower, Eloisa James: The latest in James's generally brill fairytale series! This one has elements of Rapunzel (obvy). I lurved the hero, Gowan, because he is Tall and a Virgin and SCOTTISH--his height led me to just picture Sam Winchester (IN A KILT OMGGGGGG) the whole way through, endearing him further. Since I was more into him than her--Edie, a talented cellist trapped in an era when women had to play it sidesaddle if they wanted to do so in public--I thought everybody was too hard on him in the third act. YMMV, as they say.

Pigeons, Andrew D. Blechman: You know, I don't miss much about NYC qua NYC--but I sort of love pigeons. To quote myself from Facebook: "they are honestly really pretty birds, and I think it's cool how well they've adapted to this hyperurban habitat, such that they're most of the wildlife landscape of the city. Plus, during mating season, watching the dude pigeons fluff up their feathers and do their little head-bobbing HEY HEY HEY LADIEZZZZ at the females, who never look the slightest bit interested . . . free entertainment! So hilarious." This book, then, was a goodbye-Big-Apple gift to myself. It's very much in the recent tradition of One-Subject Non-Fic (e.g. Mark Kurlansky's Salt or Victoria Finlay's Color: A Natural History of the Palette), and as such is anecdotal. Blechman visits the racing lofts of Brooklyn, the Westminster Kennel Club of pigeons shows in Pennsylvania, gun clubs that indulge in live pigeon shoots, a pair of CRAZY old ladies moseying around Manhattan dumping pounds of birdseed on the ground for city pigeons...great stuff. AND he debunks the "flying disease factory" myth that has maligned the rock dove over the past few decades: yeah, pigeon poop can breed bacteria and fungi in large quantities. But that's sort of the favorite hobby of excrement in general, isn't it? Handling a pigeon won't get you sick. SO THERE.

Red Shift, Alan Garner: THIS BOOK. Guys, I don't even know what to say about this book. It threads through three different times--Roman Britain, the English Civil War, and 1970s England--connected by a place (Mow Cop, a village on the Cheshire/Staffordshire border) and an artifact (a stone axe, 3500 years old, hidden and found between the timelines). But they're also bound by madness, and mysticism, and one of the strangest narrative flows I've ever muddled through. And I don't mean "muddled through" in a bad way, somehow--and when I say "I didn't get it, but I'm not sure there's anything to get," I don't mean there's nothing there, simply that confusion and immersion and a feeling of slipping through consciousnesses that you can't quite get a hold of are absolutely what the reader's supposed to feel. What Garner wants. It's crazy good.

Guarded (Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Season 9, Volume 3), Andrew Chambliss & George Jeanty, Jane Espenson, Drew Z. Greenberg & Karl Moline: Picked this up at Santa Fe's adorbs comics shop, Big Adventure Comics (along with the first issue of Brian K. Vaughan and Fiona Staples' Saga, which I will be reading more of POSTHASTE). I'd previously purchased Volumes 1 & 2 (Freefall and On Your Own respectively), and I've liked this season so far; it's MUCH more grounded than the whee-no-cable-budget insanity into which Season 8 devolved--and, in fact, shows Buffy finally dealing with the fact that she's never become an adult, that despite how well she handles herself with Bad Badness (in the aftermath of magic's banishment, vampires are cut off from their demonic source, and have become feral, indiscriminate butchers), she's terrible with responsibilities like jobs and rent and all the trappings of maturity. Me too, lady, me too. (The second arc features a bait-and-switch storyline that maddeningly shies away from a serious and heartbreaking decision she's faced with--and I totally understand that it was the last straw for some fans--so be forewarned. Me, I'm sort of a helpless Whedon apologist, so I'm willing to press on.)

Back in Wichita now, I'm halfway through Elizabeth Gaskell's 1865 Wives and Daughters. More to come!

24 May 2013

The Philosophy of Horror (Noel Carroll)

My husband has a degree in film from NYU (go ahead, ask him how useful it is!), so he has a few texts hanging around--including Noel Carroll's fantastic The Philosophy of Horror.

My husband has a degree in film from NYU (go ahead, ask him how useful it is!), so he has a few texts hanging around--including Noel Carroll's fantastic The Philosophy of Horror. I haven't indulged in academic writing in a while, which is a roundabout way of saying this isn't general-audience-easy to read: but it's worth the trouble indeed, for anyone interested in the horror genre and by extension the way that fiction works from a philosophical perspective. Carroll spends a lot of time of both the paradox of fiction, i.e., "How can something cause a genuine emotional response in us when we know it's not real?" and the paradox of horror fiction in particular--"Why on earth do we read/watch things that frighten and disgust us?" These chapters (2 and 4) are the most abstruse; Carroll admits in his introduction, "[Chapter Two] is the most technical chapter in the book; those who have no liking for philosophical dialectics may wish to merely skim it, if not skip it altogether." (Isn't it nice when an author gives you permission? I had forgotten my love of said dialectics until I fell back into the comforting style: "X theorizes this. But that doesn't work because of Y and Z...")

Chapters 1 and 3 are the empirical heart of the book, and the ones that will stick with me as I consume artifacts of the genre, and related ones like sci-fi/fantasy--currently, this means that during my daily binge on Supernatural, part of me checks off Carroll's criteria. First, he defines and refines the concept of art-horror (distinguished from feelings of horror elicited by real-world events), and what's required of a "monster" to be an object of this emotion. They must be threatening, obviously, but further, what he calls "impure." The latter term borrows from anthropologist Mary Douglas, who explained the impure as things that fall in between or cross the boundaries of cultural categories, creating contradiction from which we recoil. The easiest example of this is things like ghosts or vampires, who are both living and dead; but Carroll ticks off many other types of transgressive monsters: combinations like werewolves (man/beast) or China Mieville's khepri (woman/scarab); magnifications like the radiation-embiggened critters of 50s sci-fi; the incomplete, crawling hands and eyeballs and formless blobs. He argues persuasively that the fundamental feature of art-horror is cognitive threat; we react to these interstitial creatures with not only fear but revulsion.

And in chapter 3, he analyzes recurring features of horror plots--not denigrating them as formula, but teasing out the way that many stories work, in order to understand how they're satisfying. He characterizes the most common structure as "the complex discovery plot," which consists of four phases: onset (the monster begins to affect the human world, generally by killing people), discovery (the protagonist[s] begin to understand that this threat is unnatural, outside their usual experience), confirmation (often, they must convince an authority of the nature of the threat, overcoming initial resistance to the supernatural explanation), confrontation (what the Winchesters would, constantly and puzzlingly, refer to as "ganking" the monster). Of course, these four phases can be shuffled around and repeated and recombined, and some stories only use two or even one (all onset! all confrontation!). It's an absolutely marvelous theoretical framework, elegant and precise and extremely convincing.

And, you know, a great excuse to read some Joe Hill or watch some horror movies. For research.

22 May 2013

The Amazing Spider-Man, Volume 2 (Stan Lee/Steve Ditko)

My intermittent attempts to read more of the superhero-comics canon has featured some early Marvel lately. I only lasted a couple of issues into Essential Classic X-Men Volume 1, because SHEESH, Jean Grey, you have massively powerful telekinetic powers, stop putting up with these boys treating you like a rare and delicate flower. (I should read the Claremont run instead, right?)

My intermittent attempts to read more of the superhero-comics canon has featured some early Marvel lately. I only lasted a couple of issues into Essential Classic X-Men Volume 1, because SHEESH, Jean Grey, you have massively powerful telekinetic powers, stop putting up with these boys treating you like a rare and delicate flower. (I should read the Claremont run instead, right?)Thoroughly enjoyed this Spider-Man collection, though, featuring issues 11-19 and Annual No. 1, all from 1964. Honestly, I feel a little silly weighing in on heavyweights like Stan Lee and Steve Ditko, dabbler that I am--but here goes anyway: Lee's writing is sooooo fun here! So blinkin' punchy and breathless, and I downright love the braggadocio of the covers. From #16's, for instance: "Warning! If you don't say this is one of the greatest issues you've ever read, we may never talk to you again!" Hyperbole at its most charming.

And I have actual things to say about Ditko's art! I mean, obviously his human figures aren't naturalistic, and everybody's heads are alarmingly rectangular. But he's great with action and acrobatics, and varies viewing angles and framing distances, so that even conversations have a cinematic sense of movement. And I generally found it easy to follow the direction to take between speech/thought balloons in a panel, not always my strong suit.

Also, who would win in a whining fight: Peter Parker or Luke Skywalker?

16 May 2013

Deadly Kingdom: The Book of Dangerous Animals (Gordon Grice)

Recently I've been working my way through the non-fiction titles on my TBR shelf, which I often neglect. In very brief: a 60s Catholic title on true and false demonic possession, sadly not as awesome as it sounds; Peter Carlson's followup to K Blows Top, May 28th's Junius and Albert's Adventures in the Confederacy, another winner about two New York reporters shuffled between Confederate prisons before their daring escape across the Applachians; Leonard S. Marcus's winning collection of interviews with picture-book illustrators, Show Me a Story.

Recently I've been working my way through the non-fiction titles on my TBR shelf, which I often neglect. In very brief: a 60s Catholic title on true and false demonic possession, sadly not as awesome as it sounds; Peter Carlson's followup to K Blows Top, May 28th's Junius and Albert's Adventures in the Confederacy, another winner about two New York reporters shuffled between Confederate prisons before their daring escape across the Applachians; Leonard S. Marcus's winning collection of interviews with picture-book illustrators, Show Me a Story.And so I came to Gordon Grice's SUPER AWESOME Deadly Kingdom: The Book of Dangerous Animals. As the title implies, it's a compendium of the wide range of animals that are known to kill or injure humans--not just the usual suspects like lions and crocodiles and cobras, but insects that spread disease, domestic dogs that try to better their social standing by biting children, fish that leap out of the water and collide with boaters (one woman suffered a collapsed lung and five broken ribs when a sturgeon hit her), elephants that huck rocks at people (in fact, the elephant kills people in more ways than any other animal, including stomping, goring, swatting with the trunk, even sitting on them on purpose). It's encyclopedic in scope, engagingly written (favorite image: Grice's son's carnivorous water beetle darting around its aquarium "like a frantic pecan"), and a treasure trove of Fun Facts that delight my bloodthirsty inner child. Here are tidbits from all the pages I dog-eared (yeah, maybe it's a bad habit, but it meant I could find these again):

- "[The panda is] best known as the mascot of a certain conservation group and as a sexually reluctant object of human scrutiny in zoos." [25]"

- People often ask me what the most formidable predator in the world is. . . . As it happens, there is a clear answer to this perennial question, and the answer is orca." [89]

- "[The crocodile] can even slow its metabolism so it doesn't starve while waiting to ambush a particular prey item."[133]

- "In Germany, a single crow with the habit of knocking people in the head drew police to a park where, after one or two stratagems failed, they finally got the bird drunk on schnapps and arrested it." [149]

- "It has been said that if England had been as rife with chiggers as the southern United States is, English Romantic poetry might have been avoided." [179]

- "[A]bout sixty [species of millipedes] have repugnatorial glands. (The great regret of my life so far is that I have never had occasion to use that phrase in conversation.)" [182]

- Wondering why it is that butterflies are exempt from the usual insect disgust: "This thought recurs to me every time I see some painted beauty flexing its wings like a slow dream of sunset while it sips at a pile of dog feces." [207]

- Caption beneath a picture of a cutesy-wootsy bunny-wunny-woogums: "Pet rabbits have bitten off human fingers." [272]

(FYI: I read this in hardcover--the book changed publishers and title for the paperback. I like the hc cover better, because GRRRR TEETH, but you'll probably have better luck finding it as The Book of Deadly Animals, with a yellin' hyena.)

30 April 2013

NOS4A2 (Joe Hill)

So fair warning, y'all: while reading Joe Hill's 700-page new novel, NOS4A2, which you will do rapidly and with delight, you will end up with Christmas music running through your head. Constantly. And it will FREAK YOU RIGHT THE EFF OUT. William Morrow was wise to publish this in spring rather than closer to the holiday, or they'd be blamed for legions of readers having the Worst Christmas Ever--this way, the memory of Charlie Manx and his 1938 Rolls-Royce Wraith (with its titular license plate) will have blessedly faded.

So fair warning, y'all: while reading Joe Hill's 700-page new novel, NOS4A2, which you will do rapidly and with delight, you will end up with Christmas music running through your head. Constantly. And it will FREAK YOU RIGHT THE EFF OUT. William Morrow was wise to publish this in spring rather than closer to the holiday, or they'd be blamed for legions of readers having the Worst Christmas Ever--this way, the memory of Charlie Manx and his 1938 Rolls-Royce Wraith (with its titular license plate) will have blessedly faded.Charlie's car is a part of him, and he's part of it. Together, they drive down roads no other car can, all the way to Christmasland, "where every morning is Christmas morning and unhappiness is against the law." He's brought children to Christmasland for seven decades--they acquire a great many alarming extra teeth along the way--aided by a series of Renfields like Bing Partridge, who may be a few ants short of a picnic but makes up for it with his father's gas mask and a canister of gingerbread-scented sevoflurane. (Freaked out yet?)

Vic McQueen has her own uncanny vehicle: riding her Raleigh Tuff Burner at top speed, she can travel right over the Shorter Way bridge (despite its having collapsed years ago) to wherever she needs to be to find what she's looking for. One day, she goes looking for trouble, and rides all the way to Charlie, the Wraith, and the house in Colorado where Christmasland overlaps with the outside world.

And we're only 150 pages in.

I'm gonna once again break into my lockbox o' book-review cliches to pull out "tour de force," because ZOUNDS this book is good. (Interesting: a search of this blog finds that I've used the phrase previously to describe Neal Stephenson's Anathem and Dorothy Sayers's Gaudy Night. I think Mr. Hill would be OK with that company.) Hill's writing is deceptively straightforward, sly and propulsive and wise; he writes about so many things, trauma and picture books and parenthood and even Gerard Manley Hopkins and his fanboy crush on author David Mitchell, and the book is equally successful appealing to the heart and intellect as it is the hairs on the back of your neck. (While it didn't scare me quite as much as his debut, Heart-Shaped Box, that's the second scariest book I ever read, after Shirley Jackson's The Haunting of Hill House, so that ain't a criticism.) Read it now, before the radio switches over to non-stop "Little Drummer Boy," six months from now.

23 April 2013

Chess Story (Stefan Zweig)

Stefan Zweig's Chess Story is small but intense, made more so by its being the last thing the Austrian Jewish author wrote before his 1942 suicide in exile. The novella nests first-person narrators: in the framing story, a passenger on a steamer heading from New York to Buenos Aires learns he's (a presumptive he, as I don't think Zweig ever specifies) traveling with the world chess champion, Mirko Czentovic, a savant who can barely read but whose rise to the height of the chess world has been meteoric. A group of enthusiasts persuade Mirko to play them simultaneously; they fail spectacularly until they begin taking the advice of a timid stranger. This man reluctantly tells the story of how he gained his chess skills: a Viennese lawyer with ties to the clergy and the imperial court, he was imprisoned by the Nazis after the Anschluss, constantly interrogated in an effort to find the monarchic assets his firm had hidden. The preferred form of torture was total isolation--he's kept for months in a bare room, his only conversations interrogations, until he manages to steal a book from a guard's overcoat. He's disappointed to learn it's only a book of chess problems; but driven by necessity, he works through them over and over, using the checkered counterpane as a board, until he can play chess games entirely in his head, against himself . . . until the psychological task of separating his internal Black player from White overwhelms him, and he goes insane. Pushed into playing against Czentovic, he once again beings to lose his grip on reality.

Stefan Zweig's Chess Story is small but intense, made more so by its being the last thing the Austrian Jewish author wrote before his 1942 suicide in exile. The novella nests first-person narrators: in the framing story, a passenger on a steamer heading from New York to Buenos Aires learns he's (a presumptive he, as I don't think Zweig ever specifies) traveling with the world chess champion, Mirko Czentovic, a savant who can barely read but whose rise to the height of the chess world has been meteoric. A group of enthusiasts persuade Mirko to play them simultaneously; they fail spectacularly until they begin taking the advice of a timid stranger. This man reluctantly tells the story of how he gained his chess skills: a Viennese lawyer with ties to the clergy and the imperial court, he was imprisoned by the Nazis after the Anschluss, constantly interrogated in an effort to find the monarchic assets his firm had hidden. The preferred form of torture was total isolation--he's kept for months in a bare room, his only conversations interrogations, until he manages to steal a book from a guard's overcoat. He's disappointed to learn it's only a book of chess problems; but driven by necessity, he works through them over and over, using the checkered counterpane as a board, until he can play chess games entirely in his head, against himself . . . until the psychological task of separating his internal Black player from White overwhelms him, and he goes insane. Pushed into playing against Czentovic, he once again beings to lose his grip on reality.I found myself comparing Chess Story with Charlotte Perkins Gilman's "The Yellow Wallpaper," another masterpiece of oppression and isolation. They share a sense of claustrophobia and creeping horror that's astonishing in such a short fictional space. And I love how Zweig uses the mental projection required for expertise in chess as both a means of escape and a kind of psychic trap. Zweig was apparently one of the most popular authors in the world in the 1920s and 30s--NYRB Classics has translated several other titles recently, and I'll be reading more for certain.

11 April 2013

The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland in a Ship of Her Own Making & ...Who Fell Beneath Fairyland and Led the Revels There (Catherynne M. Valente)

Zounds and wow and holy cow. It is quite possible that Catherynne M. Valente's first two Fairyland books--The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland in a Ship of Her Own Making and The Girl Who Fell Beneath Fairyland and Led the Revels There--are the best middle-grade (i.e. written for eight-to-twelvers) fantasy books I have ever read. Certainly the best published this century: it ranks easily with E. Nesbit and Edward Eager, with the chronicles of Prydain and Narnia, with Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and The Phantom Tollbooth. Its most modern analogues are Dealing with Dragons and The Tale of Despereaux. And it's simultaneously influenced by all of these and utterly original.