[If I knew how to put this behind a cut, I would--it's long for this format.]

The wings had been inside her as long as she could remember. Mostly they were in her throat, when she tried to greet a neighbor or turn a phrase—beat, beat, beat, came the wings, and they blew out her breath so that she could not speak at all. When the storms came up from the coast, the wings hummed about her heart and stomach, and her mother would smooth her matted curls and coo quiet, and the wings would fold themselves away and lie still. When her mother died, the wings were everywhere—she was amazed that she stayed on the ground, stayed in one piece, for there were hundreds of wings beating her in a hundred different directions. She watched the flames from her mother’s pyre leaping, twisting, soaring to the skies, and the wings burned back in turn, beat, beat, beat.

The hooves came later, when she was eleven, kicking insistently at her chest until the flesh pointed and sagged and fell, heavy, towards the ground. They thrummed down her belly and beat like wings between her legs; she feared the coiled hair that began to grow there, feared that the hooves were driving out her guts. Then blood poured out, matting the hair, the hooves tearing her apart inside, and the blood ran down her legs. The wings came up behind her eyelids, and the tears came down like blood, and the blood came down like tears. The women of the household found her in the stable, on a clotted pile of straw, and they took her in their cloaks, in their arms, and cooed quiet. She tried to tell them of the hooves and wings but they did not understand. They told her that she was a woman now, that she belonged to them. But she knew that was not true. It was the wings and the hooves that owned her, that beat and kicked and changed her.

They took her to live at the temple. A motherless girl could not ask for more. If she could have formed the words in her throat, had it not been for the wings blowing out her breath, she would have asked to go to the temple of the Mother, to watch the holocausts and incense burn, the flames leap like wings towards the skies. But they took her instead to the temple of a god, not the father she had disappointed by the fact of her birth, but a young and handsome god, his statue covered in gold, with blue eyes like stormless skies to match the draperies his acolytes wove anew every year. She stood before him all in white, consecrated, and the hooves began to thrum below, remorselessly, on one small piece of flesh, sending flames up and down her skin that even the beating of the wings could not extinguish. She loved him. She would serve him well.

After that were days of ritual, of oil and chant and the stench of freshly killed oxen rising like flames before the god. She bowed her head as men passed by, come to the temple to pray for success in wrestling and lyre-playing; but she met the god’s blue eyes every morning, every evening, and felt the hooves thrum away till she feared the force would shatter her, cracks radiating out from the center, and she would fall to pieces like a dropped goblet.

She knew that she served the god well, more than just adequately, unlike the motherless mumbling girls beside her. She grew to look down on them, useless automatons; they spilt the oil, botched the chant, filched grapes from the god’s feast. The god would never love them as he loved her. She could fill a goblet to the very top so the strength of the wine was cut sweet with water, and she could carry the goblet high above her head, her hands wrapped in a white garment so her impure touch did not profane the god’s drink, and though she moved swiftly across the temple’s bright courtyard, not one drop of purple stained the cloth. Her length of his draperies was always a little finer than the others; she combed through the wool for hours, in secret, and palmed the best for her own use. Though she did not know the meanings of the chant—they were in a long-forgotten language known only to the high priestess—its vowels on her tongue tasted more familiar than ordinary speech. As the years passed, she looked into the god’s statue’s eyes every morning, every evening, and she could feel her love begin to pierce the stone, change the cold marble to living flesh, and she knew the god was looking back at her, not like a father, but like a lover.

So when the boy came, she knew what to do. She saw him first in all the crowd at the festival. He was perfect. Hair like gold, not just in color but in the way it bent and curled in the heat; eyes like stones made flesh. Hooves and heart and wings all leapt in every way at once, reddening her skin and causing such a headache her vision swam beneath the sun, though the boy’s outline remained clear. This was her reward, at last. Her love had brought the god to life.

When the boy looked up at her during the ceremony she looked out at him, pushing her desire through her pupils, fanned by the fluttering of wings. He did not seem the least surprised by her invitation. After all, higher-ranking women from this temple often entertained men during the spring festivals; how was he to know she was of common birth, unworthy of receiving a lover in place of the god?

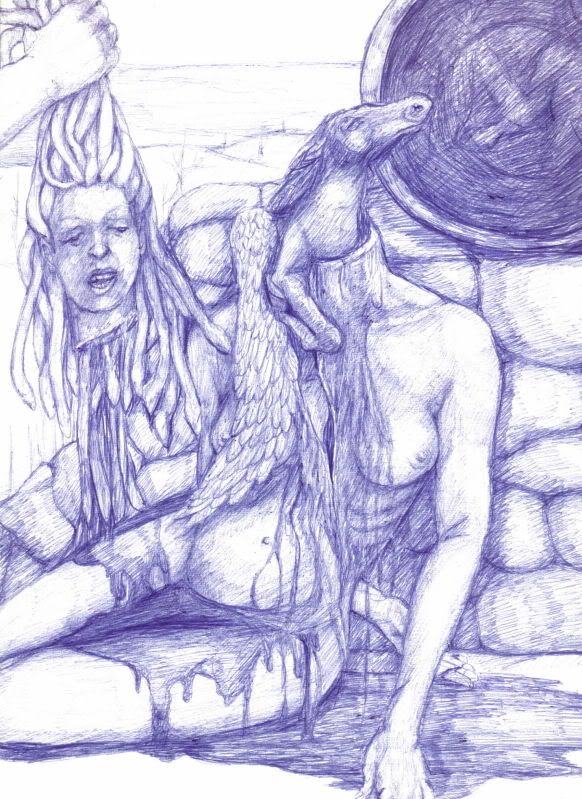

That night they met in the cedars outside the temple’s stout columns. Without a work, they clasped hands and entered the sacred place to make love in the shadow of the god. Upon the altar she rode him as if she were going into battle. "My lord!" she cried, as her wings spread full, as she gasped at the updraft that seemed as if it would carry her away; as the wings spread wide, so that she could feel each individual feather, and she reached each one, separately, to the sky.

She awoke among the virgins, at the first caress of dawn, and walked down to the river to wash. She loved disrobing under the sun which was her god’s; she shuddered at its rays, touching her like a lover. As she stepped into the water, a bird left its perch in a nearby tree and flew, warbling its morning greetings, towards her. She whistled back with joy; the bird turned its head and looked her in the eye.

And fell, suddenly deadweight, into the water at her feet.

Immediately she crouched down to touch it; immediately she recoiled. For the bird, it seemed, had disappeared; in its place lay a perfect stone replica, carved beyond any master’s skill, exact down to the smallest headfeather, the clutch of its tiny claws, as if it had died of a fright so deep all breath had fled. But beyond the strange little statue, painted on the water, was a still more incredible sight: her head, her face, contorted in shock, surrounded by dozens of writhing, black-tongued vipers.

She screamed, screamed until the noise was outside of her and she blocked her ears against it. A viper slid between her fingers, and she screamed again. The bird’s body rocked from side to side in the ripples.

She seized a rock, one of the black jewels of the volcano god, and splintered it into wafers, sharpened it frantically on the boulders of the bank. Half gagging, she seized one of the snakes on her head by its throat, pulled it taut, and began to saw at it with the makeshift knife.

And screamed again, without wishing it, at the pain that seared through her skull. Blood trickled down into her eyes; she dropped the snake to the ground, horrified, and stared at it; immediately it ceased all movement, blanched white, a companion piece to the bird who spread lifeless wings by the river bank.

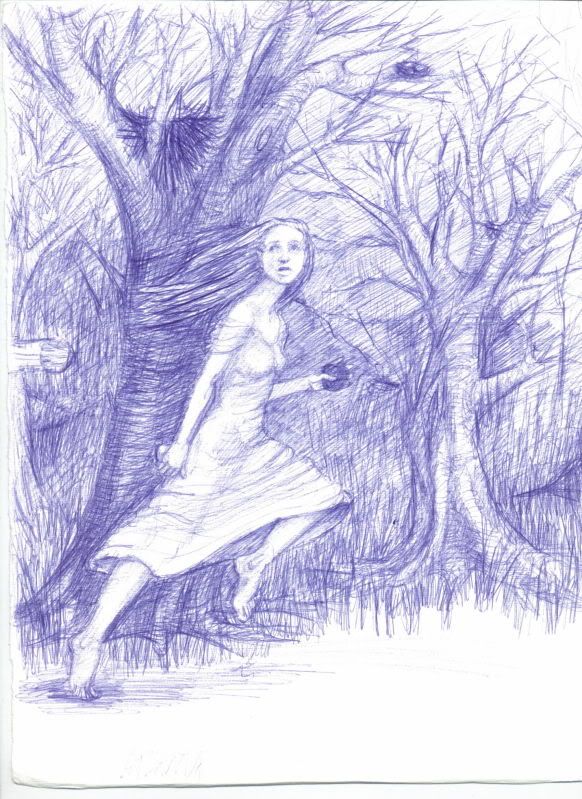

Past screaming now, she splashed water on her brow, donned her white robe, and closed her eyes. She crawled back towards the temple, feeling for the imprint of her footprints, which paced serenely in the opposite direction, away from her forever.

She would put out her eyes, she decided halfway home, like the old man in the story who could no longer look at his own life. Pausing to scrabble in the pebbles by the roadside, she found the remains of a broken pitcher, dashed to the ground by a careless traveler; she selected the sharpest shard and plunged it deep into a socket.

She vomited at the pain, and spent several minutes moaning on the ground before she realized that she could still see. She could see, in fact, the shard itself, cutting her vision in half. She pulled it out, the bile rising, and once again saw everything perfectly. The trees shuddered ashen at her approach. A line of ants with their heavy burdens turned to chips of marble under her gaze, as if a sculptor had forgotten to sweep his workshop. She put her hand to her eye and felt no blood.

Whimpering, she groped her way back; the motherless maidens had not yet arisen. From her tiny store of possessions, she selected a diadem which pinned the snakes to her skull, pulled her hood firmly up over her head. She must tell the god. Surely he would not allow this to happen to her, the most devoted of his acolytes.

Keeping her eyes firmly on the ground, she sidestepped the girl usually charged with the morning rite. "I will do it today," she said, and the girl was too young to hear the tremor in her voice.

She lit the wrong incense, the kind forbidden to all but the high priestess, the kind that allowed her to speak directly with the god. It was acrid at first, holding her head in the smoke, so that she coughed, and felt a viper jerk free and hiss in triumph; but as she kept breathing in the fumes, they became sweet, sweet like wine, sweet like blood. And suddenly she heard him; he spoke in her ear, in the voice of the snake.

"Why have you summoned me?"

She opened her mouth to stammer the proper salutations, and choked on the smoke once again. Chastened, she stared into the flame as she had seen the high priestess do—at least it continued to move as she did so—and used her heart to speak. "Help me, my lord. A terrible curse has befallen me."

"A just curse has befallen you, whore," hissed the god.

"Why? Why? What could I have done?"

"Stupid girl. You should know. You defiled my temple, my very altar, with a mortal. A worthless piece of meat, when I am your only lover."

"No! It was you, I know! I saw him. I felt it."

"You thought yourself worthy to be loved by a god?" The snake curled its body into a sneer. "A motherless girl with matted hair. You exist to sweep up the ashes, to throw the rotten food to the dogs. I would never touch you."

The wings furled themselves away. The hooves fell silent. "But I loved you. I wanted you only."

"So shall you have me. Every man you look at with your whore’s eyes will look like me. The only god you ever knew. A man of stone."

Her body fainted. Her will dragged her to the farthest corner of the temple, where she would never be noticed, and she wept the silent shrieking sobs of the brokenhearted.

Night fell. A storm was brewing, bubbling like a cauldron, off the coast. She held still for a very long time, unwilling to risk the least noise of maiden or mouse, before she opened her eyes to pitch black and breathed the barest sigh of relief. Before, she had been frightened of the dark, the way it hid life away; but this night was blessed.

She made her way to the shallow stone basin that held the god’s feast, and fell on it ravenously, olives and stale bread and watered-down wine. The girls would take it as a miracle in the morning, she realized; but she did not smile at the thought. She looked up at the god, and now in the moonlight she saw the flaking gilt, the blank blue pupils, the carved lips pressed together in a cruel smirk. Just stone. Not a man at all.

Too late. Lost in reverie, she did it all without thinking until it was too late. He reached out for her, as he had the night before, tentative but burning with need. He walked up behind her form robed white in the moonlight, in the shadow of the god, and reached out his hand toward her shoulder, the way a child reaches for the rainbow. His touch, soft but sudden, made her turn so fast her head fell back, the diadem clattered to the floor, the snakes stretched forth with a satisfied hiss, and her eyes met his, blue as stormless skies. "No!" she screamed, too late, and closed her eyes, too late, and reached out to push him away, too late, so that her hands struck hard against the stone of his shoulders. She shoved against the stone, sobbing, and finally laid her cheek against the cold of his chest, let his forever-outstretched arm hide her, and clung to him as if tears could melt the marble.

When she pulled back to look at his face, white as the temple columns in the moonlight, there was no fear on it. Instead, his eyes looked down at her tenderly; his lips, far from being twisted in terror, smiled wide and warm. It was then that she knew the worst of the god’s punishment. Even crowned by vipers, even endowed with eyes that killed sure as the moon goddess’s arrows, she was still beautiful.

***

How she got to the island she never knew. It seemed she had simply drifted there, lost consciousness and let the wings and hooves take over, and in their flight from all that was mortal and vulnerable, they had carried her body, without her knowledge, over mountain and wave, till she came to her uneasy rest on this scabrous rock, black and twisted as the snakes that slithered on her brow.

It was an island for lost things, for things that never wanted to be found. No lichen brightened its soot-black stone; no strange sea creatures of slime and tentacle dwelt in its tidepools. Even the waves seemed to break against it with undue haste, as if they, too, were eager to leave.

She named the isle Solitude on her first day, as she sought in vain a comfortable place to lay her head. The others did not come out till that first night, when she woke to four coal-red eyes in the night, and the hiss of hundreds of snakes. "Hello, little sister," they said with one voice.

Once again too late she closed her eyes tight, and heard low laughter, less mirthful than a funeral lament. "No need to hide from us, little sister," said the one voice that was two. "Open your eyes and look."

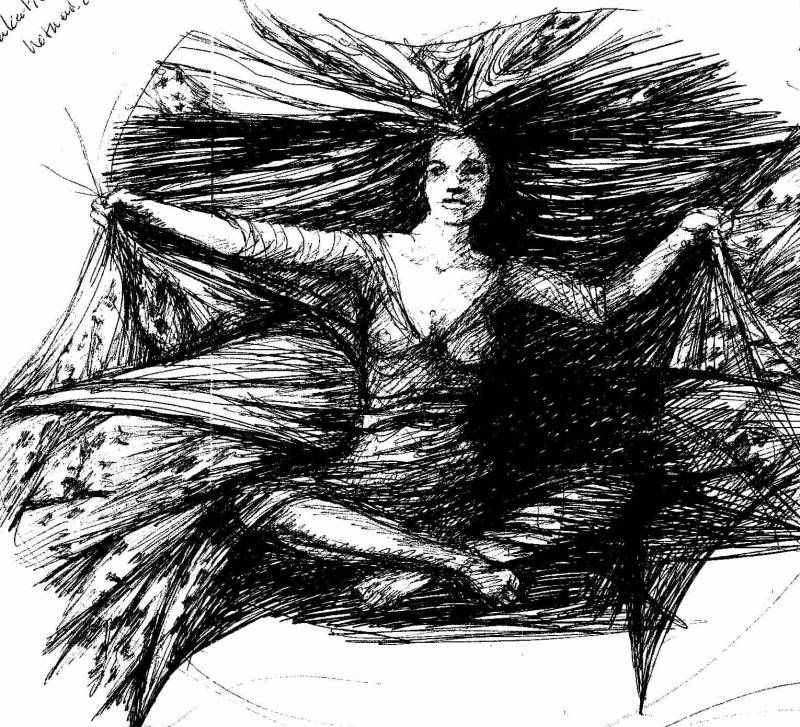

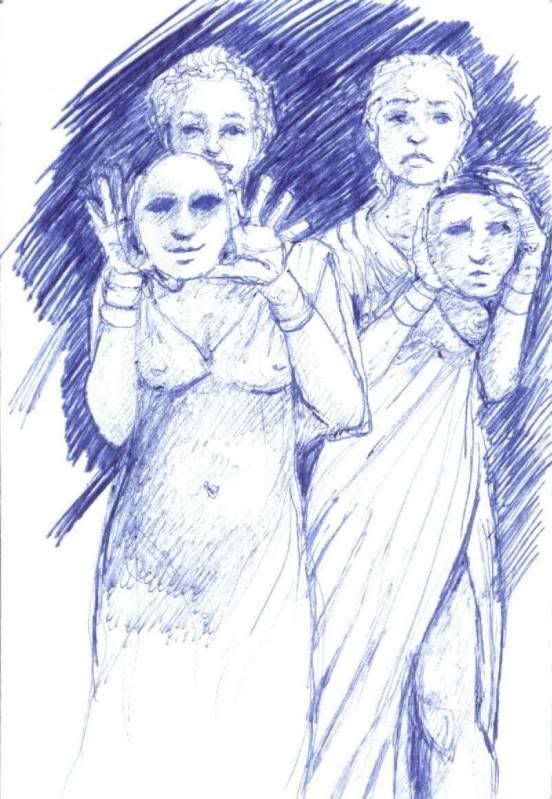

They were hideous, their faces like those of old women who had lied and hated all their years. Their eyes were red, their lips black; their hair, like hers, was nothing but vipers, who held somehow the same look of malice and deceit in their lidless eyes. Their bodies were gnarled like starved trees; their breasts hung like sacks of grain. Their skin was leprous as the rock they lay upon, mottled purple and white and green, one continuous bruise. They had wings but no feathers, rather scales, chipped and broken, wings that had never been stretched forth in the joy of flight. They were creatures of dark anger and wickedness, like the Furies of old; yet they had called her sister. Was this what she had become? Her hands went to her shoulder blades, and to her horror found there the same fleshy, reptilian wings borne by these two hags. "These are not my true wings," she cried.

"They are the wings you have," they murmured in response. "We have adopted you, little sister. You are so like us, but for your mortality. We cannot die, we who were born to this thousands of years ago. But we understand you now. We are the only ones."

"Go away!" she cried. "I am nothing like you. I am beautiful." She ran from them, dragging the ponderous wings, but the other side of the island came too soon. There was nowhere to hide. She fell to her knees, wrapped her arms around her head. She would not give in.

For a long time she did not move. They came to her from time to time, called her little sister. They never asked her to join them, and she came to know that this was because she had no choice. Alone on this blasted rock, cursed as she was, they were offering her solace, as no other being in the world could. And so one day she got up, she crossed the island, she dropped her body heavily into the nest they made of each other, their arms and legs welcomed her; she slept, and as she did she fell into their breath, one long in and out, even, uncaring. As she fell asleep, she could feel even the snakes greeting each other, twisting together for warmth, ceasing their hisses in slumber.

For a while the three women behaved like three women behave—like one soul in three bodies, flowing easily like breath between them. In her youth she completed them. They were Stheno and Euryale, and she became Medusa—the first time she had needed a name, the first time she had been more than one useless girl among many, daughters, sisters, servants of the god.

They showed her what the island concealed. It was not so featureless as it seemed. There, in the roof of their grotto, tiny jewels that never caught the light; this was what had happened, they said, when they rolled their newborn eyes to the ceiling and glimpsed the merest bits of seaweed, brought in by a tide even older than they. Here, a few steps down from Medusa’s desperate resting place, was the volcano god’s pool, which eased the mocking pain of their wings.

Her senses grew sharper as they strained for amusement. Soon she knew every inch of coastline for miles, and delighted in the greenery too far away for her to murder with a glance. Sometimes she even saw mountain goats, and once, a man, obviously a lost traveler, stranded on a crag. From him she turned her head away.

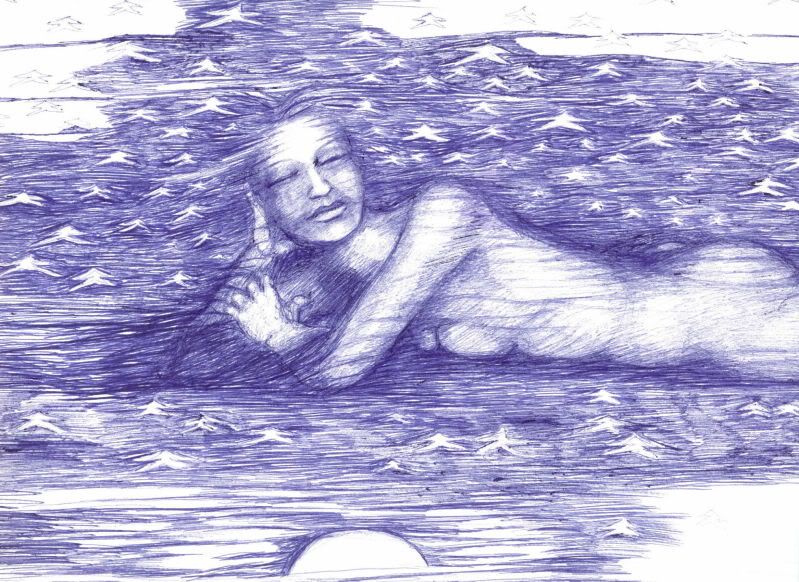

She learned to listen to the gossip of the waves, carrying news from far and wide. She learned of the great war which destroyed Ilium, flung many great heroes down to death; the waves spoke of tasting blood on the Trojan beach. The waves loved most to bubble up with stories of their lord Poseidon, and for a time they told nothing but the tales of the sea-god’s wrath, his pursuit of the man of weaving wiles, who had blinded one of his many sons. She lay on the beach and let the laughter, the anger, the wheedling of the waves wash over her.

And then one day the waves ran up the beach, to froth insistently between Medusa’s toes. News! The water was frantic with it. She followed it down by the shore; the undertow caressed her feet, held them close. The water was worried.

It told a story of a walled-in maiden seduced by gold, the father’s rage so great he sealed mother and infant in a chest and let the sea serve as executioner. But they had survived, the mother and the demi-god, and now, like so many other bastard sons of thunder, it was time for him to commit great deeds, rescue the princess, rule the people. An old tale; Medusa yawned to hear it again, and tried to shake off the sea’s grip. But it pulled tighter, sweeping her off her feet to float offshore, rocking her as if in a cradle. She must be still and listen.

This bastard son’s great deed would be to kill her, lop off her head to further his goals. Already, seethed the sea, he had tricked the Grey Sisters and knew where to find her. She must hide, hide in the grotto and never come out.

Medusa laughed at the waves’ concern. "You forget that I am a monster. He could not get close enough to behead me without being turned to stone."

Ah, but he had the help of the gods, as always, in proving himself. He had only to use a mirror; her reflection could do no harm. Her death was coming; her death was willed by the gods. The water ran down her face like tears. In her mouth, it tasted like blood.

It left her on the beach, her body covered in brine. She rose and told her sisters the news. "We will protect you," they cried. "We are immortal. We will shield you with our wings and keep you safe, little sister."

Medusa shook her head. "No," she said. "No, I think I would like to die."

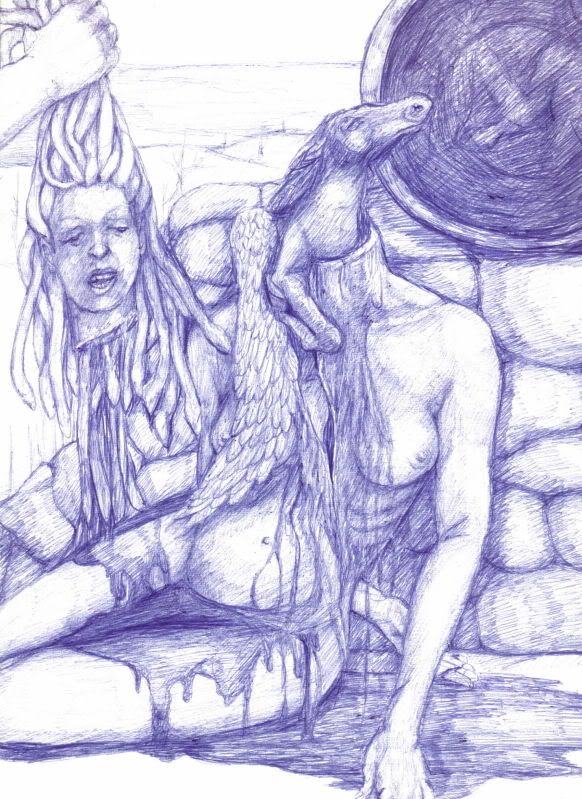

Ignoring their wails, she left the safety of the cave and strolled to a place she had once favored for scanning the southern coasts. Her knees slid smoothly into the timeworn grooves. She folded her hands demurely over the matted hair between her legs and tilted her head back to look at the sky.

He was not long in coming. She spotted him as an ungainly black speck, winging towards her on magic sandals, lurching like someone trying to run in water. She laughed at the sight, and then brought her eyes down to the sea, to allow him to approach.

He was very, very young, and he looked apprehensive but elated, like a schoolboy picked to recite in front of class. The winged sandals were too big in the sole and the wrapping went up to his thighs; the huge bronze shield and short sword he carried clanged together arrhythmically as his hands shook. She thought to herself that hers were probably the first bare breasts he had ever seen, and with a ghost of vanity she looked down at them, still poised, still white.

His hand shook, but his stroke was sure. As his blade slid through her flesh she looked up at the bronze mirror he held, and was shocked to see there the same face she had worn to greet her lover, as if only an hour had passed. She smiled.

As her body sprawled on the rock the hooves began their ascent, galloping up her spine, and the wings followed, stretching to their utmost, flexing each feather. With a triumphant whinny, the winged horse leaped from the womb that had carried it, and spreading its true wings, flew away.

[This story won Newman University's 2005 Jeanne Lobmeyer Cardenas Prize for Short Fiction. And as it turns out, my idea that Medusa was cursed for defiling a temple of Apollo comes not from actual Greek mythology but

Clash of the Titans.]